We've had an ambition to gather anecdotal material about the use of the techniques Molly teaches for some time. Finding time to do it is another story. Bringing together accounts of the use of biomechnical techniques in practice is part of the process of gathering the evidence to validate their value as an intergral part of midwifery practice. We are delighted to have someone of Heather's ability to bring things together.

Pelvic Tales - gathering the evidence to support biomechanics for birth

Heather Wilkins is a hypnobirthing practitioner, antenatal educator and doula working for The Birth Space on the Isle of Wight. Her passion for science and evidence based information was nurtured during a career with the British Antarctic Survey as a science writer. Now working with Optimal Birth, Heather is excited to be collating and sharing experiences from midwives and doulas around the world who are using their knowledge of biomechanics to support physiological birth.

Heather Wilkins is a hypnobirthing practitioner, antenatal educator and doula working for The Birth Space on the Isle of Wight. Her passion for science and evidence based information was nurtured during a career with the British Antarctic Survey as a science writer. Now working with Optimal Birth, Heather is excited to be collating and sharing experiences from midwives and doulas around the world who are using their knowledge of biomechanics to support physiological birth.

Heather has had to back off from collecting the stories because of work and family commitments but we love the way she tells the tale and really appreciate the work she put into setting up the page. If you want to share birth sotries please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

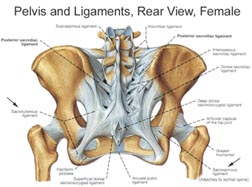

“The pelvis is the most exquisite piece of articulated architecture,” she said, with a twinkle in her eye. Molly O’Brien was opening her Biomechanics for Birth course to a room full of midwives, doulas and hypnobirthing practitioners. We could feel her passion seeping into the room and I was intrigued... what was it about the female pelvis that could get one person so fired up?

As Molly set about describing the pelvis in all its incredible form, guiding us through the sophisticated network of ligaments, soft tissues and muscle groups holding it together and explaining how their individual state can either help or hinder the function of the pelvis as a whole, a series of lightbulb moments flickered around the room. It didn't take long for us all to agree that the pelvis is an awesome piece of equipment!

As Molly set about describing the pelvis in all its incredible form, guiding us through the sophisticated network of ligaments, soft tissues and muscle groups holding it together and explaining how their individual state can either help or hinder the function of the pelvis as a whole, a series of lightbulb moments flickered around the room. It didn't take long for us all to agree that the pelvis is an awesome piece of equipment!

But the thing that struck me hardest was the realisation that a deeper understanding of the pelvis and knowledge of how to help it perform optimally during birth, can result in a significantly improved birth outcome for both woman and baby. And by this, I mean complete avoidance of intervention, assisted delivery and caesarean birth.

Mind. Blown.!

Molly’s first-hand experience of ‘unsticking’ stuck babies, sometimes at the last minute as women and birthing people awaited an imminent move to theatre, inspired and fascinated me in equal measure. It might have been a simple forward leaning inversion to stretch the uterosacral ligaments that created more space in the uterus and allowed the baby with the asynclitic head to back off from the cervix a little and get into a better position. Or perhaps a side-lying release stretched the muscles and fascia within the pelvis where the baby needed just a little more room to flex and realign, helping it to manoeuvre into a more optimal position for birth. A birthing person supported to get in to a deep squat with their feet flat on the floor could have allowed their sacrum to lift more easily – opening up the doorway for their baby to descend into the outside world. These tried and tested techniques have worked time and again.

But the birth workers in the room – who hadn’t been working with such a classy toolkit - shared experiences of a different kind. The sort that got us thinking… what might have happened if the sacrum of that birthing person with intense back pain had been enabled to lift as it should during the birth process? Could the baby have navigated its way earthside on its own, without the addition of forceps? Could the mother who was unable to endure severe pain in her pubic bone have benefited from an abdominal lift and tuck, and been able to continue contracting without an epidural? And what other ways were there to support a baby with an asynclitic head? One foot on a chair combined with a forward lunge might just create that vital bit of extra space needed for a baby to descend without its mother going through major surgery. Surely all of these techniques are worth knowing about and trying if the birthing person is willing and able.

But the birth workers in the room – who hadn’t been working with such a classy toolkit - shared experiences of a different kind. The sort that got us thinking… what might have happened if the sacrum of that birthing person with intense back pain had been enabled to lift as it should during the birth process? Could the baby have navigated its way earthside on its own, without the addition of forceps? Could the mother who was unable to endure severe pain in her pubic bone have benefited from an abdominal lift and tuck, and been able to continue contracting without an epidural? And what other ways were there to support a baby with an asynclitic head? One foot on a chair combined with a forward lunge might just create that vital bit of extra space needed for a baby to descend without its mother going through major surgery. Surely all of these techniques are worth knowing about and trying if the birthing person is willing and able.

All this left me wondering why, when midwives and birth workers are trained to support physiological birth, studies of the pelvis are rooted in a pathological sense only. Why do we not hold the pelvis in high regard and give it the respect it deserves, not only during birth but during pregnancy, too? Why are birth workers not empowered to find creative solutions for labour dystocia without rushing towards medical intervention?

Along with fear of birth and an over medicalised setting, the malposition of a baby in utero is one of the key factors that causes labour to stall. And so, if we are consistently seeing a malposition of babies in the birth room, how can we ensure that biomechanics is applied when women and birthing people are experiencing a more challenging labour?

Biomechanics for birth is not only innovative, but entirely necessary. This knowledge and expertise should not be limited to the very few. It makes complete sense, to me, that anyone training in the art of supporting birth should have access to this quality education.

And this is why I am excited to work with Molly. Through the power of storytelling we hope to inspire, educate and inform birth workers around the world so that they, too, may learn the art of biomechanics for birth.